Health

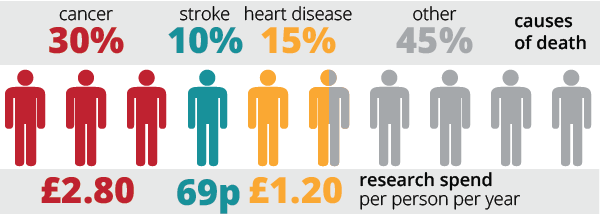

Cancer kills almost a third of us, and yet we spend less than £3 per person per year researching it. (And it’s arguably the best-funded medical condition.)

Looking at other big killers paints a stark picture of the state of UK medical research funding. Let’s look at government spending on diseases, compared to the number of people killed by them.

Heart disease is responsible for around 15% of deaths, and yet we spend just £1.20 per person per year researching it. Stroke is the third most deadly individual condition, responsible for 10% of deaths; stroke research receives just 69 pence per person per year. So, astonishingly, these three conditions are responsible for over half of the deaths in the UK, and yet we invest less than £6 per person per year to try to understand their causes and find new treatments.

Medical research is a special case in science, because charities make a significant contribution—in fact, over half of UK medical research into cancer, heart disease and stroke is charity-funded. The combined figure for public and non-profit research into these three conditions is around £13 per person per year, which still seems feeble compared to their deadliness.

Looking at mortality statistics starts to give a sense of scale to measure up health research spending, but what doesn’t kill you can nonetheless have a huge effect on your quality of life. Therefore, it would be a mistake to concentrate all our research on the most fatal conditions. For example, dementia has a massive effect on quality of life, but the condition itself is rarely fatal. It affects one in six people over 80; we spend about £1.20 per person per year researching it.

The suffering caused by illness should be reason enough to invest more seriously in looking for treatments. However, diseases also come with a significant economic cost. Firstly, there’s the substantial direct cost, in terms of health and social care for sufferers. Secondly, there are large indirect costs, such as friends and family members taking time off work to care for loved ones. The total economic impact of the four diseases mentioned is over £800 per UK citizen (split between everyone, not just patients) per year. This makes the combined £6.50 (£13 with charities) each we spend researching all four of these conditions look rather paltry.

The total investment in health research also looks tiny compared to overall government spend on healthcare; government, EU and charity research investment comes to less than £60 per person per year, whereas UK healthcare spend is around £1,900—and that’s before we take into account any of the other economic or human costs of ill health. If we want to reduce these costs and improve our health, we should increase the sum devoted to research.

Ageing

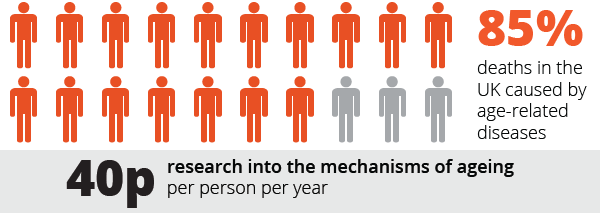

It’s not only research into individual diseases that is important, however. Cancer, heart disease, stroke and dementia, along with many other conditions from diabetes to macular degeneration, are all known as ‘age-related diseases’: they disproportionately afflict older people. In fact, more than 85% of deaths in the UK occur due to such conditions.

It’s well-known that the elderly are at greater risk of death and disease, but by just how much is quite surprising. For example, between the ages of 25 and 34, you’ve got a 1 in 1700 chance of dying annually (in large part due to accidents and self-harm). However, between the ages of 75 and 84, the annual risk of death has gone up nearly 100-fold. In fact, the risk of dying in a given year increases exponentially as you get older: it roughly doubles every seven to eight years. This massive increase in risk is due largely to the increased burden of age-related diseases.

Your increased susceptibility to these diseases arises from the process of ageing. Biologically speaking, ageing comprises an accumulation of a variety of molecular and cellular junk in our bodies, and the effects of this junk are what make these diseases so common in the elderly.

Finding ways to slow the accumulation of age-related damage, or fix it once it has accumulated, could provide broad-spectrum protection against a range of age-related conditions, and significantly improve the health and happiness of our ageing population. This is a serious possibility: we’ve been doing it successfully in lab animals for decades. Unfortunately, research in this area is hampered by an equally serious lack of investment: we spend around 40p per person per year investigating the ageing process. If we want to unlock the huge potential benefits of ageing research, we must increase this investment.

From ageing, to energy: the next section looks at the economic and environmental consequences of our tiny investment in energy research.