Cash, shares or science?

Research generates discoveries and saves lives, but is it good for the economy? In the run-up to the Government’s Autumn Statement on November 23rd, we’ve created some infographics for Science is Vital and Scientists for EU, to make the case that science is an important investment.

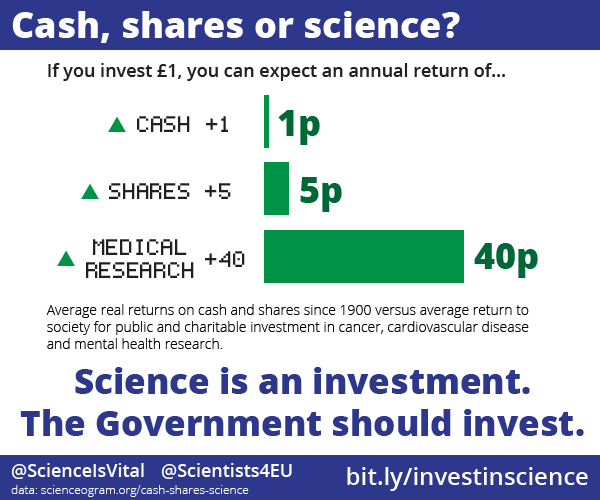

Here’s the first one:

This graphic pits returns from investment in science against returns from two other common investments—cash and shares—and shows that research really does knock it out of the park in terms of financial savvy.

The cash and shares figures come from the latest edition of the Barclays Equity Gilt Study, which tracks returns on investment in government bonds (gilts) and shares (equity) since 1900.

Though it’s not usually the same as the interest rate you’ll get on your savings account at any given point in the last 100 years, so-called Treasury bills are often used as a proxy for long-term investment in cash. By this measure, the ‘real’ return on cash savings—after correcting for the effect of inflation— is a somewhat paltry 1p per year on a pound saved.

Shares fare somewhat better, and typically return 5p per pound per year, though obviously they come with increased risks: as the cliché goes, ‘investments can go down as well as up’. This 5% is thus a (very) long-term average, but it provides a benchmark for what an investor can reasonably hope to make in the long run, assuming they’re comfortable with uncertainty.

So, what about science? It’s harder to estimate the returns on research because they’re not neatly tallied up in a century of stock exchange records. This means that economists have to do it the hard way. They tallied up the total amount spent on research in three areas: cardiovascular disease and mental health (in a 2008 paper entitled ‘Medical research: What’s it worth?’), and cancer (in a 2015 sequel). They then looked at treatments developed, and estimated the money and years of healthy life saved by them, as well as the returns to the wider economy. The return on £1 invested was equivalent to 39p for cardiovascular disease, 37p for mental health, and 40p for cancer research, every following year.

Of course, this isn’t directly comparable to returns on cash or shares. For a start, as an individual, you can’t directly invest in ‘research’ and reap the benefits. Those gains are recouped by society at large, not any one person or company. There’s also huge uncertainty on numbers like these, and the economists acknowledge this, whilst checking that changes in the underlying assumptions don’t drastically alter their conclusions. However, it’s obvious that, even if this 40p estimate is wildly inaccurate, it’s still a stonking return on investment. This figure would have to be out by a factor of ten for shares to be a better bet.

According to the Equity Gilt Study, the government can expect to borrow money in the long term for around 1.2% interest. (At the moment, rates are significantly lower than the historical average, meaning that the UK government can borrow even more cheaply than that.)

If you, as an individual or the owner of a business, could borrow money at 1% interest and make a 40% return, it would be a no-brainer. This, in a nutshell, is the economic case for government funding of science.

It’s important to remember that the economic argument isn’t the only one when it comes to funding research, from hard science to the arts and humanities. Whether it’s saving lives or the abstract joy of discovery, there are plenty of other good reasons to invest. We also shouldn’t see this as a call to invest only in research whose commercial upside is immediately obvious. Much of the research included when calculating the 40p return was so-called ‘basic’ or ‘blue-skies’ research, which has no immediate application but often underpins research which does. It’s impossible to know in advance which projects will be the useful ones but, even in the absence of that knowledge, the return on research overall remains compelling.

So, if Philip Hammond is serious about ‘taking careful, considered and targeted decisions around very high value infrastructure investment opportunities’ and ‘taking advantage of low borrowing costs, and our ability to borrow long term’, science should be on his shortlist next week.