Research is Great, but investment is declining

Last week, the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) released an infographic announcing that Research is Great: Britain is an international bastion of highly efficient scientific research. Just two days later, the Office for National Statistics released a bulletin showing that UK investment in research and development has fallen for the first time in two decades.

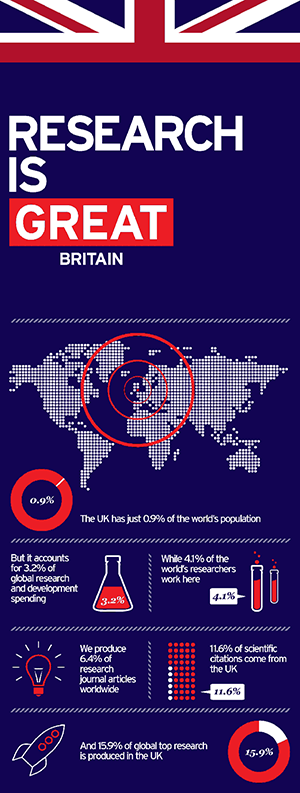

First, the BIS infographic: owing something of a debt to a graphic in a 2010 report by the Royal Society, it walks readers through a series of successively increasing percentages illustrating that British research punches above its weight by a variety of different measures. With less than 1% of the global population, the UK is nonetheless responsible for 3% of global R&D investment, which results in nearly a sixth of ‘top research’ (defined as publications which are cited a large number of times) hailing from UK shores.

There are, however, a number of ways to read this graphic. For example, with just 0.9% of the world’s population, the UK is responsible for 3.4% of global GDP: our investment in research is in large part a function of our relative global wealth. In fact, since our 3.2% share of global R&D spending is less than our 3.4% of GDP, this simple measure would seem to imply that we’re underinvesting in science and innovation! Further, since Britain is responsible for 3.2% of global R&D and yet 4.1% of the world’s researchers, does this mean that our scientists are underpaid, or comparatively underequipped on the global stage? Aggregate figures like these don’t allow for detailed analysis, but questions like these are begged.

That said, as measured in terms of publications, the UK is clearly a very efficient scientific nation: we produce around twice as many as you’d expect for our investment, and five or six times the number of ‘top’ journal articles. So, with a system so obviously efficient per pound spent, we might hope that the government would be increasing investment to capitalise on this efficiency, and reap the economic and social benefits of scientific research and technological development.

So, we turn to the annual update of the so-called Gross Expenditure on Research and Development (GERD) statistics from the ONS. This document shows that UK investment in research is on a downward trajectory.

The new numbers bring the dataset up to 2012, and illustrate that R&D spending decreased by almost all measures since 2011—the first such decrease since data began in 1995. Total GERD dropped by 3% when adjusted for inflation, whilst public-funded research fell by nearly 7%.

Putting these figures into an international context, UK GERD as a fraction of GDP in 2012 was just 1.72%: significantly below the EU-28 average of 2.06% for the same year. This erodes our already unimpressive performance internationally.

Of course, as with the statistics in the Research is Great infographic, these kinds of aggregate numbers don’t allow for particularly detailed analysis. But, however you read them, these figures aren’t encouraging. As Prof James Wilsdon, Professor of Science and Democracy at the University of Sussex told The Conversation, ‘Whatever we think about the pros and cons of GERD ratios, we shouldn’t see twelfth place in Europe as an acceptable ranking for one of the continent’s leading economies.’

The government clearly acknowledges the UK’s strengths in science and technology, but the statistics show that pithy infographics and kind words from the Chancellor have yet to be translated into increased investment, and this is why it’s vital that we make science funding a political issue.